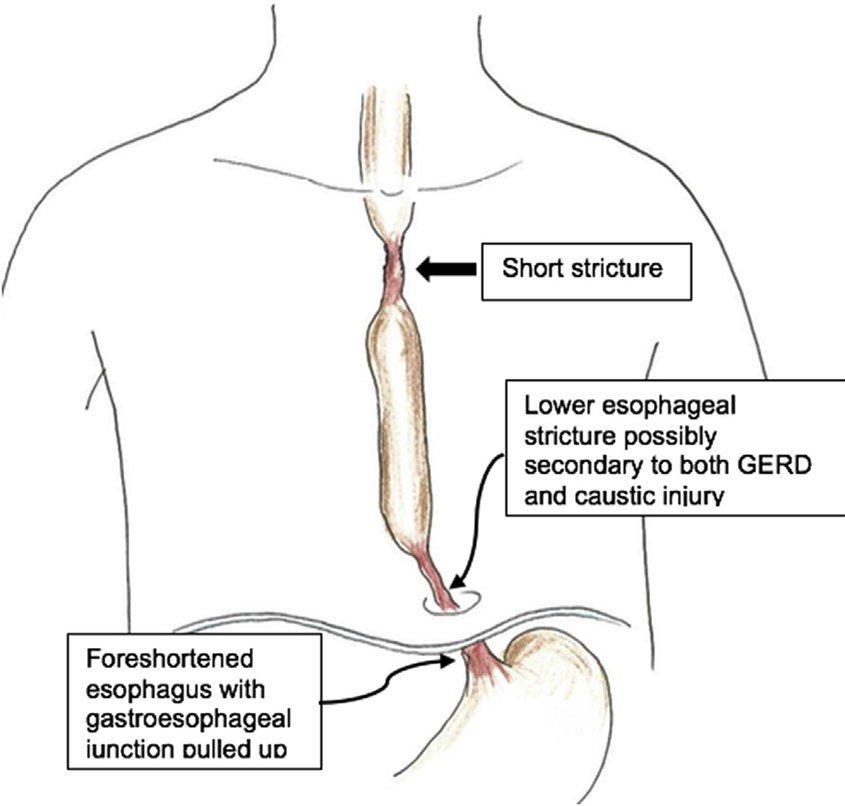

An esophageal stricture refers to the abnormal narrowing of the esophageal lumen. It often presents as dysphagia commonly described by patients as difficulty in swallowing. It is a serious sequela to many different disease processes and underlying etiologies. Stricture formation can be due to inflammation, fibrosis or neoplasia involving the esophagus and often posing damage to the mucosa or submucosa.

Etiology

A stricture is either benign or malignant. The majority of esophageal strictures result from benign peptic strictures from long-standing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which accounts for 70 to 80% of cases.

Benign Strictures

- Persistent reflux of gastric acid

- Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma)

- Corrosive substance ingestion

- Drug-induced esophagitis: Many medications can cause pill-induced esophagitis. Common culprits include NSAIDs, potassium chloride tablets, and tetracycline antibiotics, among other medications.

- Esophageal surgery

- Protracted use of a nasogastric tube

- Eosinophilic esophagitis: It represents a distinct chronic, local immune-mediated esophageal disease clinically characterized by dysphagia and histologically by eosinophilic-predominant inflammation.

- Radiation therapy to the chest or neck

- Esophageal damage caused by an endoscope

- Treatment of esophageal varices

- Infectious esophagitis – Candida, herpes simplex virus (HSV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

- Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and immunosuppression in patients who have received a transplant

- Crohn disease – Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory disease of the digestive tract

Malignant Strictures

- Esophageal adenocarcinoma

- Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Metastatic esophageal neoplasm – usually from lung cancer

Pathophysiology

The normal esophagus measures up to 30 mm in diameter. A stricture can narrow this down to 13 mm or less, causing dysphagia. The pathophysiology of stricture development differs based on the underlying etiology, but the basic pathological changes include damage to the mucosal lining. Over time, this leads to chronic inflammatory changes in the wall of the esophagus. Chronic esophagitis progresses even further with subsequent development of intramural fibrosis and scarring, leading to luminal constriction.

Malignant stricture develops from intrinsic direct proliferation and invasion of cancer cells from the luminal mucosa.

Symptoms

- The most relevant symptom is progressive dysphagia to solid food, and this sometimes progresses to involve semisolid and liquid foods

- Chest pain after meals, increased salivation

- Regurgitation of foods and liquids. Sometimes the patient may report having water brash, morning soreness of throat or asthma-like wheezing, which may be due to severe regurgitation

- Regurgitation may aspirate into the lungs, causing cough, wheezing, and shortness of breath

- Weight loss and anorexia along with long-standing weakness are more associated with malignant strictures or refractory strictures

- Sensation of something stuck in the chest after you eat

- Heartburn

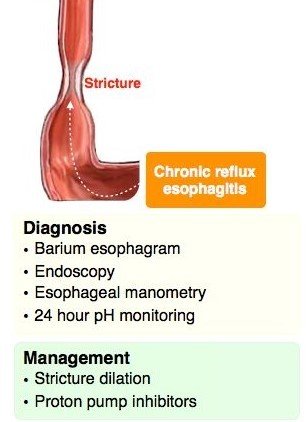

Diagnosis

A medical history and physical examination are performed.

Barium swallow test

It can show the abnormality in the esophagus and provide an understanding of level, size, extent, and severity of strictures, especially when standard endoscopes cannot pass through the stricture and thin-caliber scopes are not available. Barium contrast swallows are found to have 95% sensitivity for diagnosing esophageal stricture. The radiographic appearance of a stricture differs based on the underlying etiology.

UGI Endoscopy

Upper GI endoscopy is the most important diagnostic and therapeutic intervention in the case of a stricture. After the presence of a stricture is confirmed, the most important step is to biopsy the stricture to rule out malignancy.

Endoscopic Ultrasound

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can provide high-resolution images of the esophageal wall, and it can provide detailed information about the extent of the esophageal injury in other benign causes of stricture.

Esophageal pH monitoring

This test measures the amount of stomach acid that enters your esophagus. Your doctor will insert a tube through your mouth into your esophagus. The tube is usually left in your esophagus for at least 24 hours.

Management

Any stricture requires treatment to establish adequate luminal patency. Various methods and instruments are used to achieve this goal. Treatments include the use of dilators, stent placement, surgical resection, and medical management.

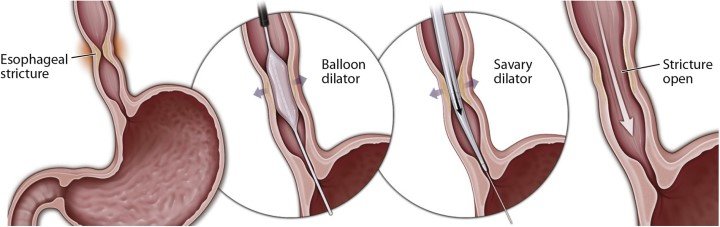

Stricture Dilation

There are two types of dilators.

Mechanical (push type or bougie): They come with a variety of sizes and are made up of different types of materials such as rubber. Maloney bougie dilator can be freely passed without the use of the guidewire. While Savary-Gilliard has a guidewire to assist in the passage.

Balloon: Expansion of a balloon produces radial force to dilate the lumen. Different sizes are available, and a balloon dilator gets passed through the scope (TTS). Newer balloon dilators from having an inbuilt guidewire and also allow for three different size expansions without changing the balloon.

Stricture dilation is an ambulatory outpatient procedure that requires certain levels of expertise from an endoscopist.

Esophageal Stents

Stents are often reserved for malignant stricture and refractory benign strictures. The goal of stent placement is to hold the stricture open for prolonged periods, causing the stricture, or the tissue around it, to remodel so that the stricture does not recur after stent removal. In malignant stricture, this could be either used for complete palliation in case of advanced cancer or temporary palliation in cases of ongoing neoadjuvant treatment

Medication

A group of acid-blocking drugs, known as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), The PPIs used to control GERD include:

- omeprazole

- lansoprazole

- pantoprazole

- esomeprazole

Antacids: provide short-term relief by neutralizing acids in the stomach

Sucralfate: provides a barrier that lines the esophagus and stomach to protect them from acidic stomach juices

Antihistamines (such as ranitidine and famotidine): decrease the secretion of acid

Surgical Management

Surgical resection is reserved for malignant disease-causing esophageal stricture or benign conditions recalcitrant to less aggressive forms of medical and/or endoscopic therapy. When surgery is necessary for benign refractory peptic strictures, an antireflux procedure is selectively done to prevent further stenosis. Otherwise, palliative surgical approaches are considered to relieve symptoms or obstruction and to provide a route for enteral nutrition distal to a stricture, usually via gastrostomy tube placement.