Madura Mycosis

Introduction

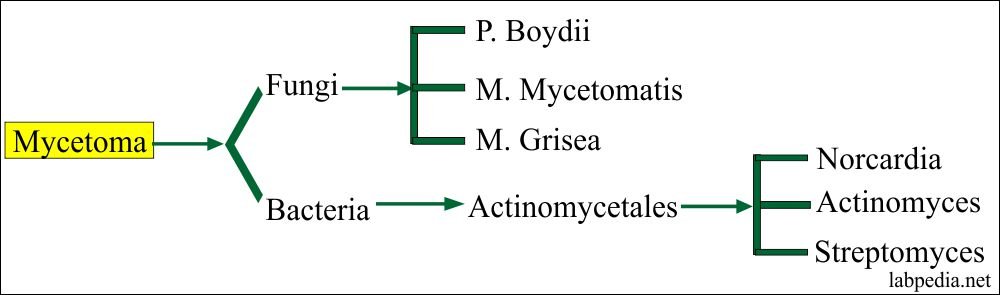

Maduromycosis was first discovered in Madura, India, between 1842 and 1846. It predominantly affects the feet which are infected by a penetrating trauma. Eumycetoma is a disease that is usually found in the tropics; only a few cases have been reported in temperate climates. The organism has been isolated in soil and on thorns, the most likely sources of infection. Infections often develop in people who have contact with soil, work outside, or frequently engage in outdoor activities. Some cases of human to human transmission have also been reported. Mycetoma is produced by a number of organisms: eumycetes, or true fungi, and actinomycetes, or false fungi, which is a filamentous bacterium.

The organism that is usually responsible for maduromycosis in the United States and Canada is Petriellidum boydii; in Africa and India, it is Madurella mycetomi; in Mexico, it is Nocardia brasiliensis, and in Japan, it is Nocardia asteroides. Maduromycosis is rare in the United States.

Pathogenesis

Mycetoma is more common in males than females and generally affects adults.

It is also mainly seen in agricultural workers, although this is not invariable. There is evidence that the organisms are spread from the environment via a penetrating injury such as thorn implantation. The fungal causes of mycetoma have been isolated from plants, plant debris and soil; Nocardia species have been isolated from soil. Mycetoma organisms possess mechanisms that aid survival in the human host allowing them to evade immune defences. Some of the mechanisms of adaptation include the deposition of intra- or extracellular melanin, cell wall thickening and immunomodulation.

Clinical Features

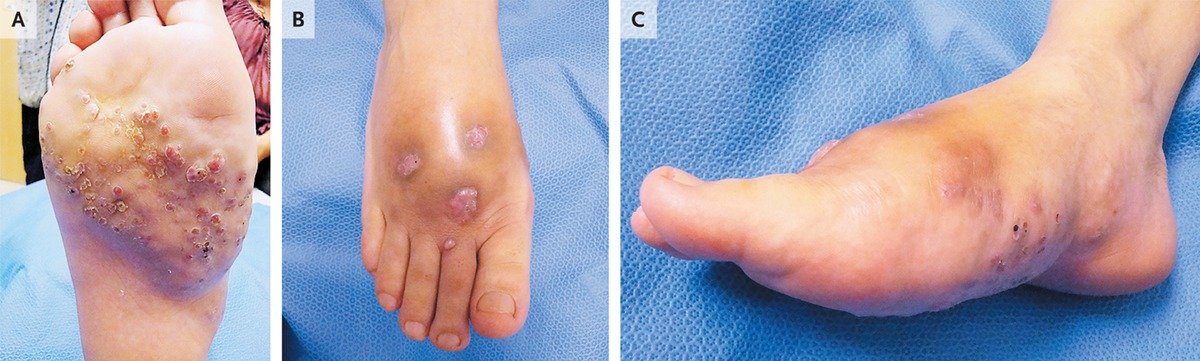

Earliest sign : Appearance of a small symptom-free dermal or subcutaneous swelling. With time this slowly enlarges and sinuses appear on the surface of the nodule. Pain may occur prior to rupture of sinuses on to the skin surface which in the early stages heal up.

Chronically discharging sinuses are formed in well-established lesions and there is considerable woody swelling affecting the site, accompanied by deformity.

The main areas affected are feet, lower legs and hands. Dissemination is rare, although some infections may become very extensive and spread widely over a limb. The only threat to life is where they involve the skull.

Radiological changes : include cortical thinning or hypertrophy, periosteal proliferation and lytic lesions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most accurate method of delineating the extent of lesions.

Differential Diagnosis

- Osteomyelitis caused by bacteria or actinomycosis.

- Botryomycosis

- Chromoblastomycosis

- Sporotrichosis

Laboratory Diagnosis

Demonstration of grains of the organisms which are generally obtained by opening a sinus where there is a small amount of pus beneath the skin surface, using a sterile needle. The grains can usually be seen with the naked eye in the pus and blood coming from the sinus tract.

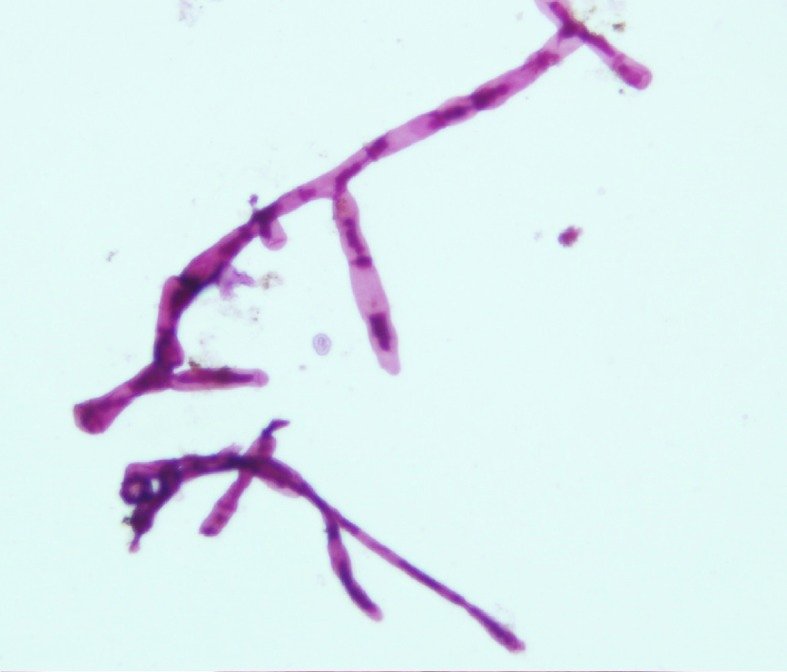

Direct microscopy. Grains are mounted in 5–10% potassium hydroxide (KOH). They are gently squashed. As a general rule if the filaments can be seen with the ×40 objective the cause is a fungus. However, if these are not visible the cause is likely to be an actinomycete. Actinomycetes under the microscope usually show branching filaments, abundant aerial mycelium, and long chains of spores.

Grains can be taken directly from sinuses for histology and embedded after formalin fixation. The appearance of many grains is typical in haematoxylin and eosin stained sections and the use of special fungal stains such as periodic acid– Schiff or methenamine silver is not strictly necessary.

The ZN staining technique is superior in discriminating between actinomycotic agents; Nocardia spp. are ZN positive, whereas A. madurae and S. somaliensis are ZN negative.

Grains can be cultured on a variety of media and the appearances of the fungi or actinomycetes are typical, although a specialist laboratory will be needed for their identification. Sabouraud agar supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract, blood agar, brain–heart infusion agar, and Löwenstein agar are the commonly recommended media.

If grains cannot be obtained by this method a deep and wide biopsy is necessary and the specimen submitted for histology and culture.

A main aim of laboratory diagnosis is to separate fungal and actinomycete causes because the treatment of each is different.

Management

The treatment of mycetoma depends on knowing whether the cause is an actinomycete or a fungus.

The actinomycetes respond to a variety of antibiotics such as sulphonamides and sulphones or co-trimoxazole. For many infections it is advisable to use a second drug such as rifampicin or streptomycin. Alternatives include amikacin, ciprofloxacin and imipenem for difficult cases. Several weeks of treatment may be required.

Treatment of eumycetomas is more difficult. About 40–50% of infections due to Madurella mycetomatis respond to an azole such as ketoconazole 200–400 mg daily, itraconazole (200–400 mg daily) or voriconazole (400 mg daily). Therapy may need to be continued for over a year. Although surgery remains an option, the most effective operation is amputation and if the patient is not incapacitated by the infection.

Reference: Uptodate and Clinical mycology